The actin cytoskeleton contributes to essential processes across eukaryotes. Our current understanding of the actin cytoskeleton is based on experiments that were performed using just a handful of species. While most cytoskeletal research has aimed at understanding human health, researchers have discovered and characterized many components using single-celled organisms. For example, capping protein and the branched actin-nucleating Arp2/3 complex were first identified and purified from the single-celled amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii

Recent work has illuminated unique characteristics of the actin cytoskeleton in unicellular, green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, which expresses two separate compensatory actins and lacks any known activators of the Arp2/3 complex

The cytoskeleton varies greatly across the tree of life.

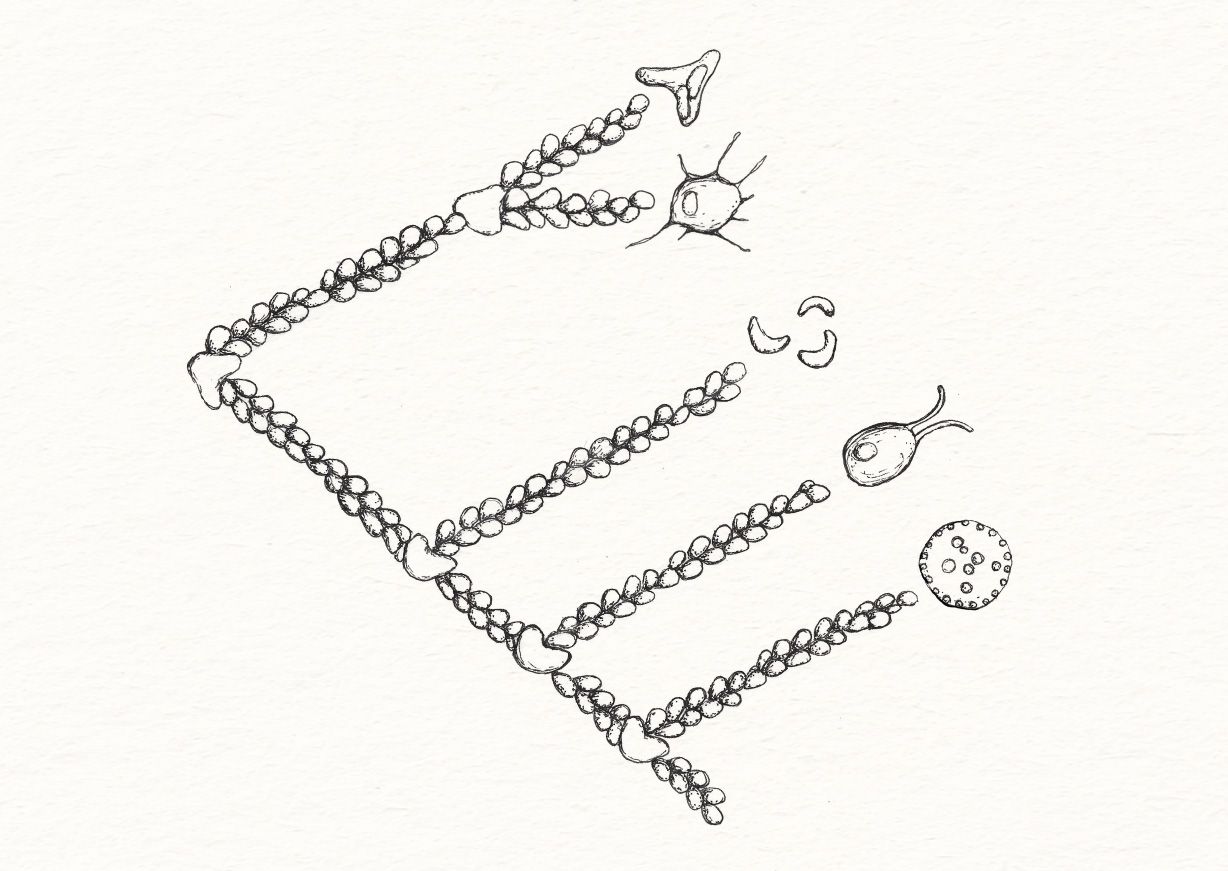

We're exploring the actin cytoskeleton and its regulators in species like Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Bigelowiella longifila, Raphidocelis subcapitata, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and Volvox carteri.

The following questions guide this project:

- Can we identify novel actin regulators in diverse species lacking canonical regulators?

The spatial and temporal regulation of actin filament assembly, disassembly, and modification is essential across eukaryotes. Many of the proteins responsible for regulating these processes are conserved across species; however, recent work has uncovered that several organisms lack clear homologs to these important regulators

- Can we uncover novel actin-dependent functions using diverse organisms that carry out unique cellular processes?

Actin filament polymerization is essential for many essential cellular functions, including division, adhesion, and motility

Actin polymerization is important for cell motility, usually through the formation of branched actin networks at the leading edge of crawling cells. Many microalgal species have cell walls and move instead by microtubule-based flagellar motility. However, some members of the chlorarachniophyte family perform both flagellar motility and amoeboid motility

Learn more about these findings:

Chlorarachniophytes form light- and Arp2/3 complex-dependent extensions that are involved in motility and predation

Long protrusions from several microalgal species appear to help cells move, capture prey, transport mitochondria and chloroplasts, and more. Are they filopodia that evolved abilities more like other actin- or microtubule-based structures, or are they something new?

The actin cytoskeleton contributes to the structure of many cells. Many algal species have unique and intricate morphologies, especially diatoms. Phaeodactylum tricornutum is one of the first diatoms with a sequenced genome and is found in three main morphotypes, making it an ideal species to study. Interestingly, while this species has homologs to actin and various actin-binding proteins, it lacks homologs to the Arp2/3 complex subunits. Surprisingly, we observed several P. tricornutum cells forming protoplasts and separating from their cell wall when treated with the myosin II inhibitor (-)-blebbistatin and the Arp2/3 complex inhibitor CK-666. However, our recent attempts to replicate these findings have been unsuccessful, likely due to the sensitivity of cell wall-less protoplasts under harsh conditions. We share our findings, with caveats about reproducibility in the pub below:

Inducing protoplast formation in Phaeodactylum tricornutum by silica deprivation, enzymatic treatment, or cytoskeletal inhibition

Treating P. tricornutum cells with serine endopeptidases or certain cytoskeletal inhibitors induces the formation of cell wall-free protoplasts and suggests a novel role for actin and myosin in preventing protoplast formation.

We ultimately realized that it would be challenging to experimentally answer the key questions presented here without broader comparative analysis. We’ve pivoted to building computational pipelines that we can apply more broadly to discover genes involved in pathways we care about or to predict novel functions in general. We’ll follow up on some of what we find in the lab. Because of this shift, we’ve decided not to continue this experiment-based approach any further.