Nature contains remarkable diversity, and the answers to many impactful biological questions are likely hidden within this diversity. By comparing the shared building blocks that make up all organisms, including the DNA, protein, and other components of cells, and identifying similarities and differences, we can make hypotheses about the answers to those questions.

Our team is particularly interested in the comparative biology of proteins because DNA sequencing methods are rapidly advancing and producing mountains of high-quality protein sequence data. However, protein sequences are frequently only as useful as their functional annotations, and predicting a protein’s function remains a bottleneck in the meaningful analysis of protein sequence data

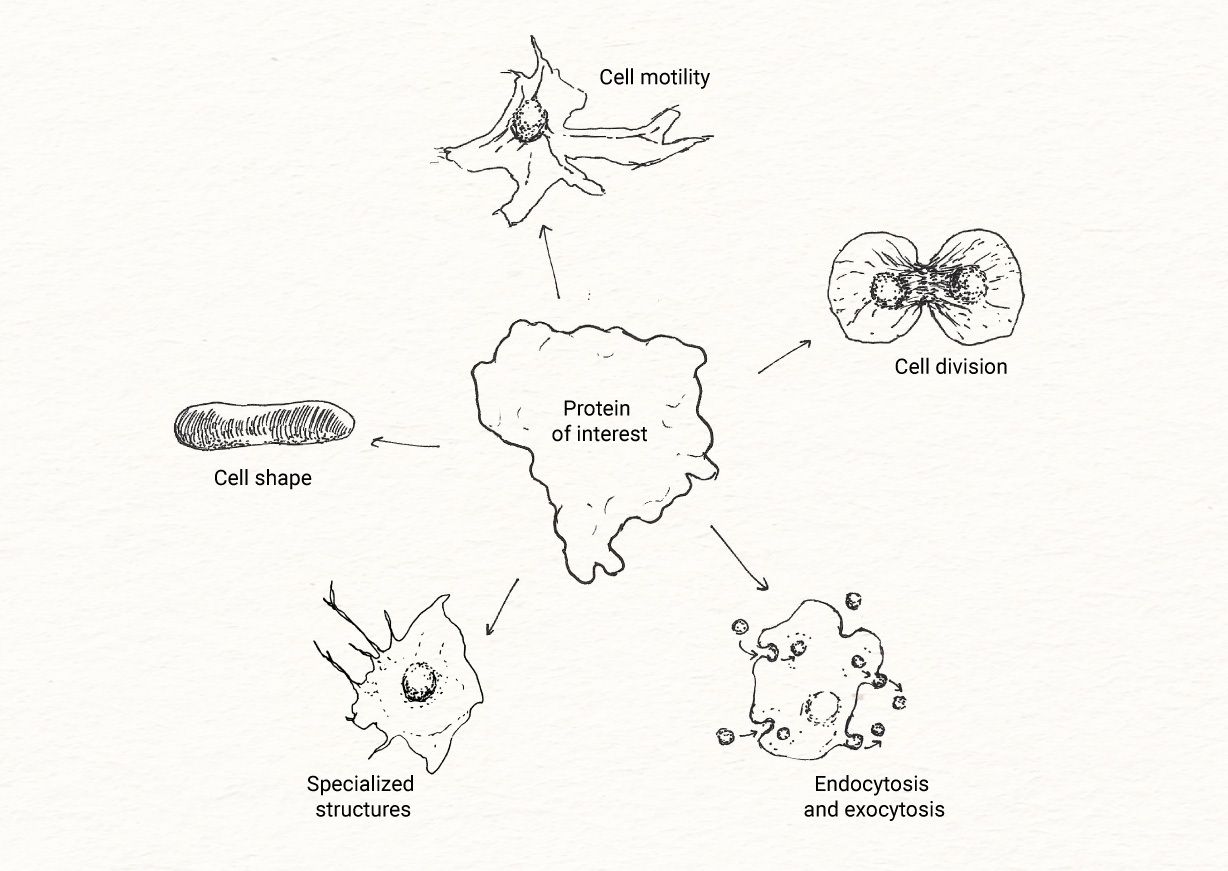

Cellular functions can define protein identity.

We are developing a framework to computationally predict and validate annotations based on protein functions. These annotations should help scientists uncover novelty and generate hypotheses.

Most annotations are based on information gathered in a small selection of organisms. In fact, 85% of Gene Ontology annotations are based on information from just ten species, including humans and other typical model organisms

Researchers are now developing computational approaches that take into account protein sequence, structure, and even interactions with other proteins or co-expression patterns to annotate new protein sequences

To overcome these obstacles, we’re building tools that combine experimental data with computational predictions to compare proteins and provide functional predictions to inform our annotations. Our hypothesis is that using this type of comparative analysis and functional annotation framework can help us identify interesting proteins with unusual characteristics that may have novel functions and interactions.

Our overall goal is to create user-friendly, customizable workflows and tools that compare protein families in diverse organisms in a deep and functionally meaningful way. This will empower scientists to answer their research questions in the best way possible using the right organisms and the right proteins.

We can break this down into a handful of guiding principles:

- Our work should be usable by researchers both at Arcadia and outside Arcadia. Whether we are creating computational workflows or biochemical studies, we are developing tools with users and their questions in mind.

- We want our work to foster organism inclusivity by working equally well for any organism of interest. In other words, we want to use all available data to create a space that is as representative of the tree of life as possible.

- This work should enable scientists to learn more about the most important part of proteins — how they function.

- We want our tools to be hypothesis-generation machines. We want to leverage comparative biology and capture the dark areas in protein space to find the novelty that can lead to the next great ideas.

Our first dive into the functional annotation space was to test how reliable existing annotations are and to show that one way to deeply understand a protein family is to combine sequence, structural, and functional comparisons.

To do this, we chose to use actin, which is important for a number of essential cellular functions

Thus, this test case can tell us about a long list of cellular functions, but could also help us answer fundamental biological questions about what else actin might be doing in cells. Beyond that, this work helped us define what really must be conserved for proteins to share functions (sequences, domains, structure, etc.) and helped us create a framework that we and others can use for higher-throughput identification of proteins based on functional characteristics. Finally, this demonstrates that annotations even for well-studied families are not always reliable.

Learn more about this effort:

Actin: Can incorporating additional functional information into ProteinCartography maps help us create better hypotheses?

The process of deciding whether a candidate actin homolog represents a “true” actin is tricky. We propose clear and data-driven criteria to define actin that highlight the functional importance of this protein while accounting for phylogenetic diversity.

In this pub, we use protein structural comparisons to explore protein families with the goal of helping users generate new hypotheses about what features could be driving functional differences within protein families and predict which proteins might be especially interesting for further analysis.

We created ProteinCartography, a Snakemake pipeline that compares protein structures at the family level for rapid and intuitive analysis. The pipeline starts with your favorite protein(s), identifies similar proteins using sequence- and structure-based searches

This pub contains the initial version of the pipeline with core functionality, but we will continue to improve, and we welcome any feedback either directly on the pub or in the GitHub repository referenced therein.

ProteinCartography: Comparing proteins with structure-based maps for interactive exploration

The ProteinCartography pipeline identifies proteins related to a query protein using sequence- and structure-based searches, compares all protein structures, and creates a navigable map that can be used to look at protein relationships and make hypotheses about function.

To gain confidence in our tools, we’ve used several protein families as test cases. These analyses have each told us something new about how our tools work and they’ve generated a number of hypotheses that could tell us a lot about these protein families.

One of the first use cases of this tool was to investigate why some bacterial species accumulate more polyphosphate than others. This is an important area of interest for wastewater treatment, and so far it has been difficult to predict which bacteria will be better at accumulating polyphosphates. We used ProteinCartography, along with other tools, to test whether protein structural similarity among PPK1 enzymes, which catalyzes polyphosphate formation, might be able to help solve this question.

In addition to helping us learn about polyphosphate accumulation and PPKs, this work also helped us learn more about how to incorporate bacterial analyses into ProteinCartography, which was originally more eukaryote-focused. It also helped us connect phylogenetic comparisons and protein structure analysis to generate more informed predictions.

Discovering shared protein structure signatures connected to polyphosphate accumulation in diverse bacteria

Only some bacteria accumulate substantial amounts of polyphosphate (polyP). We thought that despite sequence divergence, polyP synthesis enzymes in these bacteria might have similar structures. We found this is sometimes true but doesn’t fully explain the phenomenon.

Inspired by a comment on that work, we released an “open question” pub to spur engagement with the broader community about future directions in polyphosphate accumulation.

How can we identify the common molecular signatures underlying polyphosphate accumulation?

Since releasing our pub on polyphosphate-forming proteins in bacteria, we’ve noticed the community has similar problems studying this process in diverse organisms. We’re actively seeking feedback with a focus on advancing basic discoveries and useful tools in this space!

In another use case, we combined ProteinCartography and the results of our analysis looking at important functional residues in the actin family. In our “Defining actin” pub

Because the actin family is so well studied, this was a useful test case for ProteinCartography. We were able to show that proteins generally sorted into their expected subfamilies (actins clustered together, actin-related proteins clustered together, etc). However, there’s plenty of room for discovery even in this well-studied protein family, and we developed a list of testable hypotheses. We pursued one of these hypotheses in “A structurally divergent actin conserved in fungi has no association with specific traits” (described next), but we’re sharing the rest here with hopes that the community will run with them.

Exploring the actin family: A case study for ProteinCartography

We’ve applied ProteinCartography, a tool for protein family exploration, to the well-studied actin family. We’re able to categorize actins and related proteins into distinguishable functional buckets, and we uncovered some surprising hypotheses that could prompt further study.

As described above, applying ProteinCartography to the actin family suggested several avenues for follow-up study. One intriguing observation was a cluster of actin-like proteins that, in addition to being structurally divergent from canonical actin, are primarily found in fungal species. We wondered if these structural differences were related to functional differences linked to a specific fungal trait.

We first confirmed that these divergent actins are indeed mainly present in fungi. We then applied phylogenetic trait mapping to investigate the relationship between their presence and specific fungal traits. Any correlation could suggest a specific function for these proteins. We explored six traits, which spanned ecology, fungal structure, and genetics. The presence or absence of this divergent actin did not correlate with any of the traits we analyzed.

That said, trait data was limited, constraining the scope and power of our analysis. We remain optimistic about the potential for phylogenetic trait mapping as a tool for functional annotation and discovery in future studies.

A structurally divergent actin conserved in fungi has no association with specific traits

We outline a comparative approach to investigate protein function by correlating the presence or absence of a protein with species-level phenotypes. We applied this strategy to a novel actin isoform in fungi but didn’t find an association with any of the phenotypes we considered.

We designed this set of use cases to help us validate our protein functional prediction tools, especially ProteinCartography, in vitro. ProteinCartography, a tool for structure-based clustering of protein families, could be useful for predicting protein function. However, we first needed to test two hypotheses to be confident in these predictions: 1) proteins clustering together based on structure have similar functions and 2) proteins in different structure-based clusters have different functions.

Our overall strategy for in vitro validation of ProteinCartography requires answering four questions, including how we select protein families, how we select protein clusters and individual proteins, and finally, which functions to test in the lab.

A strategy to validate protein function predictions in vitro

We aim to validate ProteinCartography, a tool for structure-based protein clustering, by evaluating two foundational hypotheses: that proteins within a cluster have similar functions and proteins in different clusters have differing functions.

For our first round of validation, we selected protein families that had previously been characterized biochemically and produced ProteinCartography results with clearly defined clusters we could use to test our overall hypotheses. We selected two protein families: Ras GTPase and deoxycytidine kinase.

Ras GTPase is an extensively studied protein superfamily of small monomeric GTPases. They’re involved in many signaling pathways in the cell and have been implicated in a number of cancers and other diseases. In addition to their critical biological roles, they’re small, structured, and have assays available to test biochemical functions. We asked for feedback on how to narrow down clusters and individual proteins to focus on for our biochemical analysis and how we might functionally characterize proteins from this superfamily.

How can we biochemically validate protein function predictions with the Ras GTPase family?

We’re using the well-studied superfamily of small monomeric GTPases, the Ras GTPases, to evaluate our structure-based clustering tool, ProteinCartography. We’re seeking feedback on working with this protein family and determining which individual proteins to study.

Deoxycytidine kinases are a group of well-studied proteins involved in the nucleoside salvage pathway. They’ve been used to help with cancer and viral therapies. Additionally, these proteins are small, structured, and have commercially available assays that produce a wealth of data we can use to test our hypotheses. Like Ras GTPases, we also sought feedback on how to narrow down which clusters and individual proteins to focus on.

How can we biochemically validate protein function predictions with the deoxycytidine kinase family?

The human deoxycytidine kinase, a member of the nucleoside salvage pathway, has been studied extensively. We’ll use this family to assess our structure-based protein clustering tool, ProteinCartography. We’d love feedback on how we might work with this protein for validation.

We moved forward with deoxycytidine kinases. We selected two clusters and compared proteins from both within each cluster and between them. We found that the structural clustering aligned with functional data in some cases, but not always. For example, proteins within one cluster always acted most strongly upon a single substrate. However, proteins in the other cluster we analyzed had more mixed specificity, but tended to act more broadly than the proteins in the original cluster. Overall, we found that ProteinCartography can be a useful tool to make predictions about function, but it should be used alongside other analyses.

Structure-based protein clustering sometimes, but not always, provides insight into protein function

We asked whether ProteinCartography’s structure-based protein clustering reflects functional features of proteins. We found that proteins often clustered with proteins that have similar functions, but there were cases when this wasn’t the case.

We plan to apply these pipelines to work happening at Arcadia. We hope you’ll use them as well, and let us know if you have thoughts for the future of the work by commenting on our pubs. To try out the actin pipeline, visit the GitHub repository here. To try out the ProteinCartography pipeline, visit the GitHub repository here.

We’re also exploring new protein-based analyses that leverage evolution by using proteins from across species for specific purposes, like protein design. Stay tuned for updates related to this!