We believe that ticks have much to teach us about our own biology. Ticks are ancient parasites that co-evolved with humans and have developed their own sophisticated molecular toolkits for extracting blood through our skin. Unlike other blood-feeding parasites, ticks feed for days at a time on the same host while evading detection. This is in contrast to other parasites, including mosquitos and fleas, which only need to feed for seconds at a time and can be detected upon skin breach.

This suggests that ticks have evolved extremely sophisticated ways of manipulating all kinds of processes in our skin barrier (sensory pathways, immune response, blood flow, wound healing, etc.). We are interested in mining tick saliva for the molecules that carry out these functions so that we can leverage them for novel therapeutic interventions. To do this, we need some basic tools in place to assay for the activities we are interested in and to identify the specific molecules responsible for these activities.

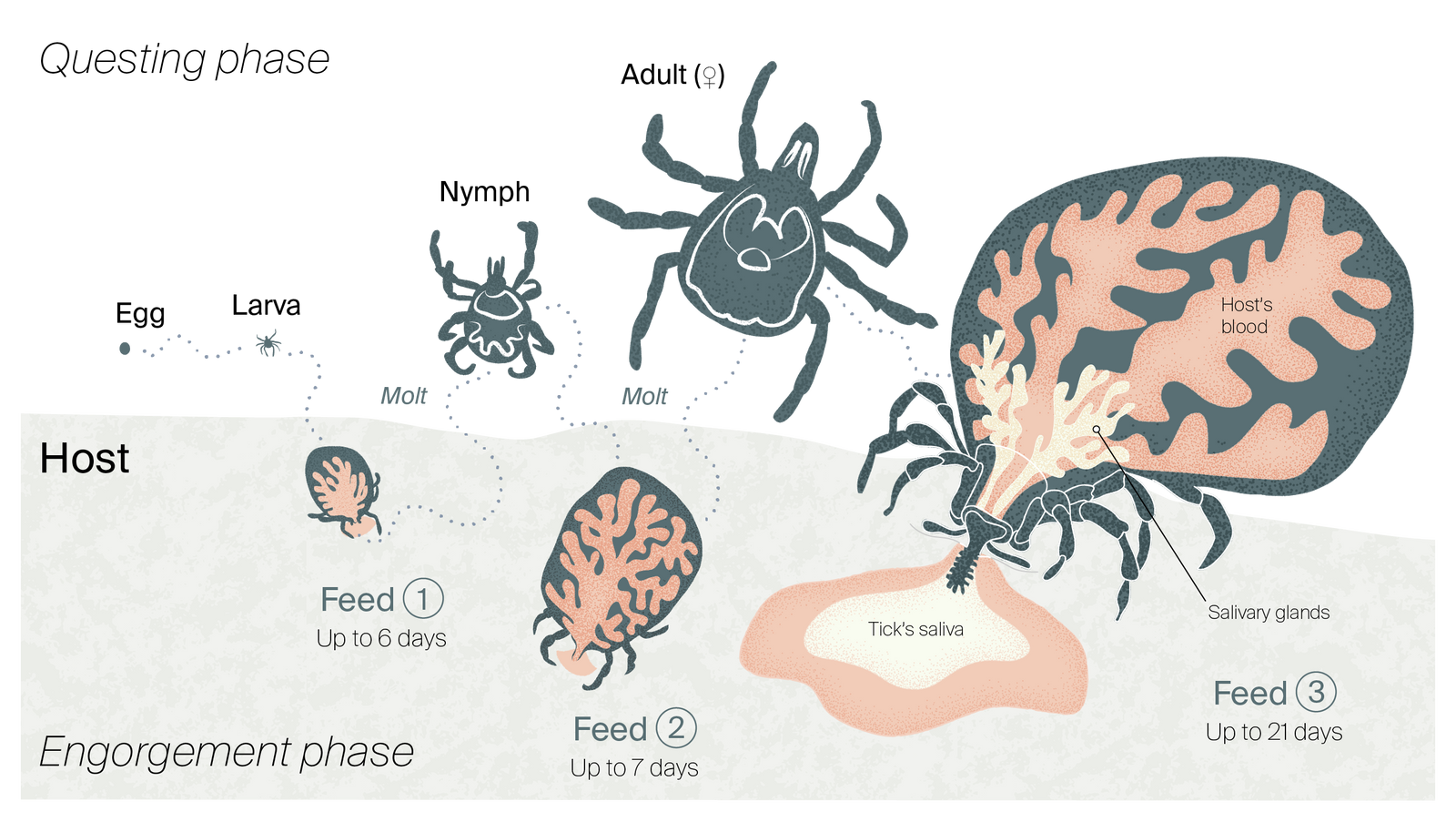

The three-host life cycle of the lone star tick, A. americanum.

- Develop mass spectrometry pipeline for protein identification (proteomics)

- Develop mass spectrometry pipeline for small molecule identification (metabolomics)

- Develop assays to screen for activities of interest

A few guiding concepts in how we’re thinking about this project and why we’re sharing each part of our work:

-

It’s very hard to do mechanistic work in new organisms without some basic omics in place, but usually the people exploring new organisms don’t have the resources or expertise to perform sophisticated omics analyses or know what tradeoffs exist at each step.

-

This work isn’t always documented.

-

Different groups use different references, which makes it hard to compare results. Many scientists don’t even realize the degree to which reference quality for proteomics can totally change what the results look like — are we even comparing apples to apples?

One of the first things we had to do was figure out how to do molecule discovery in tick species for which there was very little existing omics information. Most of the omics work in ticks has focused on one species, due to its critical role as a disease vector: the blacklegged tick (or deer tick), Ixodes scapularis, which transmits the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. For our purposes, we want to survey a broader range of tick species to access a bigger pool of bioactive molecules that regulate our skin, focusing on species known to attach and feed on humans. For many of these, such as Amblyomma americanum, there was not a fully assembled and annotated genome. This inherently limits the kind of proteomic analyses we can do, given that mass spectrometry-based identification of proteins relies on the mapping of protein fragments (peptides) against protein sequences that are typically predicted from genomic information. Thus, we had to solve this problem quickly. We also had to figure out the most generalizable way to do it so we could survey broadly across many tick species.

First, we considered sequencing the tick genomes. Unfortunately, tick genomes tend to be several gigabases large (similar in size to the human genome), so we decided to avoid genome sequencing and assembly in favor of a simpler approach. After conversations with Joan Wong (CZ Biohub) and Elizabeth Tseng (Pacific Biosciences), we saw a path forward through long-read transcriptome profiling using Pacific Bioscience’s Iso-seq method. This approach to RNA sequencing provided us with the full structures of tick transcripts without assembly. We could then use these transcripts to identify protein-coding sequences, which formed the basis of our proteomics database.

The method we ultimately developed should be broadly useful for any species that lacks reference omics data. Read more and access a detailed protocol here:

Performing mass spectrometry-based proteomics in organisms with minimal reference protein databases

If you’re interested in generating proteomics data but your organism of interest doesn’t have a sequenced genome to use as a reference database, it is straightforward and useful to collect a transcriptome instead.

Figuratively speaking, this was our first time at the rodeo. We were excited when the slew of data arrived, but we knew little about genome/transcriptome completeness assessment. Juliana Gil (UC Davis) came to the rescue and taught us about how the BUSCO software package could help our efforts. According to BUSCO, our transcriptome and associated proteome were found to be mostly complete. We used our new proteome dataset to map peptides to mass spectra in order to identify proteins in our own complex Amblyomma americanum lysate. Gratifyingly, we were able to make a number of peptide-mass spectrum assignments that were not previously possible.

Read more about our Lone star tick data set and access the data itself here:

Robust long-read saliva transcriptome and proteome from the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum

The way you generate a reference database has a real impact on the completeness and results of proteomics experiments.

In addition to soliciting direct comments on our pubs, we decided to speak directly with other scientists in the tick community.

On June 8, 2022, we hosted a Zoom session with tick researchers to discuss our recent pubs, pain points in tick omics, and possible future solutions. We also discussed the results of our Twitter poll asking which tick species we should apply omics tools to next (the winner: Ixodes scapularis). We’re super grateful to Januka Athukoralage, Matthew Butnaru, Nsa Dada, Joao Pedra, Agustin Rolandelli, and Isobel Ronai for their time and for all of their great input!

Below is a distillation of the items we touched on in problem-solution format.

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Several hundred tick species are known, but Ixodes scapularis is the most well-studied. Based on our poll results, the community still wants a high-quality reference genome and accompanying transcriptomes because the current reference datasets are inadequate. These types of references are generally scarce or non-existent for other tick species. | The Pal lab is currently developing new references that could significantly improve the Ixodes scapularis landscape. These references could provide exactly what our poll respondents are requesting, which means we may be able to move on to the second most voted-on tick species: Ixodes pacificus. |

| Genome and transcriptome annotations are important for advancing tick biology at a molecular level. High-quality annotations are not broadly available and are major bottlenecks for tick biology (this is even true for Ixodes scapularis). | Long-read transcriptomics tools might provide better information about gene structures. Additionally, there may be a way to work backwards using proteomics data to improve annotations at the transcript and genome levels. This is something we can begin exploring in the near future. |

| Protein functional annotations are of mixed quality as tick genomes encode many proteins of unknown function. | Better gene annotations would enable better high-throughput functional assays for characterizing genes of unknown function. |

| There seems to be a reluctance around exploring the biology of other tick species and more broadly, non-model organisms. This may be due to biases carried over from prior training experiences and funding pressures. Without a critical mass of researchers building and sharing tools and data, it can be daunting to establish the groundwork necessary to study a new organism with satisfying depth. | A fellowship program encouraging post-doctoral level trainees to build tools at Arcadia could help lower barriers around the study of non-model organisms. Researchers could carry these tools forward, giving them a head-start in career development. |

Ultimately, we’ve realized that there may still be many proteins in our lysates that remain unidentified if we rely solely on our transcriptome as a reference. This could be a consequence of inadequate transcriptome sampling depth or because those proteins’ corresponding genes were not actively transcribed during our tissue harvest. We decided to use PacBio HiFi long-read sequencing to generate a reference genome for Amblyomma americanum, which will hopefully enable a more complete decoding of the proteomics mass spectra we’ve obtained so far. We present our first draft assembly in this pub:

De novo assembly of a long-read Amblyomma americanum tick genome

We generated a whole-genome assembly for the lone star tick to serve as a reference for downstream efforts where whole-genome maps are required. We created our assembly using pooled DNA from salivary glands of 50 adult female ticks that we sequenced using PacBio HiFi reads.

However, genomes alone aren’t enough for protein identification since they contain both protein-coding and non-coding sequences. We need gene models to help us differentiate between these types of sequences if we want to use this as a map for identifying proteins. Unlike genomes, transcriptomes specifically include expressed copies of coding sequences.

Therefore, we used publicly available and in-house-generated transcriptomes from A. americanum to guide our gene predictions. Our resulting gene models were comparable in quality to other reference tick genomes, such as Ixodes persulcatus. In our pub below, we describe details of our approach, including transcriptome assembly, microbial decontamination of the draft genome, gene model prediction, and follow-up validation analyses:

Predicted genes from the Amblyomma americanum draft genome assembly

We previously released a draft genome assembly for the lone star tick, A. americanum. We’ve now predicted genes from this assembly to use for downstream functional characterization and comparative genomics efforts.

Once we’d predicted genes for A. americanum and had lots of transcriptomic data (from our own work and that of others), we got curious about how A. americanum uses its genes under different conditions. By learning which genes are expressed when, we can start to make better predictions about their role in tick biology. In the pub below, we re-analyzed public RNA-seq data from A. americanum to investigate differential gene expression across variables such as sex, tissue type, and feeding time. We explored gene expression patterns and created an interactive Shiny app that lets researchers look at these results. This tool highlights expression patterns in key tissues, like salivary glands, and allows for insights into gene activity under different conditions.

An interactive visualization tool for Amblyomma americanum differential expression data

We analyzed RNA-seq data from Amblyomma americanum to explore gene expression linked to skin manipulation during tick feeding. We built an interactive app to explore the differential expression results and find patterns related to tick sex, tissue, and time in blood meal.

With these foundational resources in place, we’ve moved on to our next phase of work: mining for therapeutically useful molecules. We decided to take two different approaches in parallel.

First, we’re pursuing a classic empirical strategy of fractionating physical tick samples and experimentally testing them for activities of interest. This approach not only takes advantage of the omics resources we’ve refined but also lets us find small molecules that aren’t directly encoded by individual genes. Updates are forthcoming, as we’ve been incubating our first promising startup based on some exciting discoveries from this work.

We’re also taking a second, more computationally-focused approach. Instead of empirically following bioactivities of interest, we think we can hunt down therapeutically useful molecules in ticks by looking at evolutionary patterns of their gene families. Why? As ectoparasites, ticks have evolved novel, sophisticated molecular strategies to manipulate our skin defense systems and sensory processes. Evolutionary innovation like this leaves behind genomic signatures, and our hypothesis is that we can follow these breadcrumbs straight to treasure.

As we previously laid out on one of our platform pages, we’ve been building an end-to-end, open-source workflow for phylogenetic inference called NovelTree

Read more about our initial search predicting protein families involved in suppressing host itch, pain, and inflammation here:

Comparative phylogenomic analysis of chelicerates points to gene families associated with long-term suppression of host detection

We investigated patterns of gene family evolution across ticks and other parasites. We used phylogenetic profiling and trait-association tests to identify gene families that may enable parasitic species to feed on hosts undetected for prolonged periods.

We also predicted peptides from these protein families and nominated a set for laboratory testing against mast cells, though we ended up icing this line of inquiry due to limitations of the assay.

Read about our peptide predictions here:

Predicting peptides from tick salivary glands that suppress host detection

We predicted tick salivary gland peptides that may help the tick evade host detection while feeding. Using phylogenetics and peptide prediction, we identified 12 candidates. However, testing the trait in the lab proved challenging, so we aren’t continuing the project.

Read about mast cell assay concerns here:

Compound 48/80 is toxic in HMC1.2 and RBL-2H3 cells

We found that compound 48/80, an MRGPRX2 agonist and commonly used in vitro mast cell activator, is toxic in HMC1.2 (human mast cells) and RBL-2H3 (rat basophils). Researchers should use caution and incorporate a viability test when performing assays in these cell lines.

Our goal is to understand how ticks manipulate their hosts (us!), with the aim of reverse-engineering these strategies to inform new treatments for dermatological diseases. However, experimentally characterizing parasite effector proteins is slow and challenging work, which limits the number of tick effectors we can mechanistically dissect. Ideally, predicting the target of tick effectors computationally should allow us to design more targeted wet-lab experiments and computationally map the targets of effectors across a much wider range of parasites.

As a first pass, we ran a small case study with a family of tick protease inhibitors to see if we could use AlphaFold-Multimer to computationally narrow in on the potential host proteases targeted by these proteins. However, the results we got from this case study weren’t that compelling. Some targets seemed reasonable (i.e., present in the skin and involved in itch and inflammation), but others were less relevant to tick biology (i.e., human digestive enzymes). We aren’t sure if this reflects the real biology or a high false-positive rate. Without a better understanding of the strength of our predictions, we’re reluctant to invest more resources in this approach by following up experimentally or scaling across more parasites.

How confident should we be in potential targets of tick protease inhibitors predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer?

We want to predict the targets of tick effectors to identify new therapeutic targets for skin diseases. We ran a case study using AlphaFold-Multimer to predict the targets of tick protease inhibitors, but we aren’t sold on our method. What other approaches should we consider?

In parallel to applying AF-Multimer as a tool to predict the targets of parasite effectors, we’ve also explored protein structural mimicry as an orthogonal approach to identify potential targets of parasite effectors. We initially got interested in mimicry because we found that tick IL-17-like proteins and tick SAA-like proteins may modulate host detection of parasites. Mimicry is a useful pointer to potential host targets: when a parasite effector structurally mimics a human protein, it strongly suggests the parasite protein will have some of the same interaction partners as its human counterpart. We built a mimicry detection pipeline and benchmarked it on well-studied viral mimics.

A method for computational discovery of viral structural mimics

Some parasites use mimics of host proteins to manipulate host pathways. We’ve developed a mimicry detection pipeline and benchmarked it using well-studied viral mimics. The pipeline successfully recovers known mimics and is ready for deployment at scale.

In addition to our computational search, we pursued an orthogonal strategy of experimentally searching for anti-itch activities in ticks. We took a classical process-of-elimination approach by fractionating lysates from A. americanum and testing them for activity. The advantage of this approach is that we don’t have to narrow our list of possible candidates a priori, and we can really prioritize the activity we most care about. This allows biology to tell us what might matter.

However, in the absence of any clear molecular or cellular assays that report directly on itch, which is the culmination of numerous neurological and immune pathways, we believed our best option to be in vivo mouse scratch assays that tell us if there’s a phenotype at the behavioral level. We moved forward with a previously developed scratch assay, customizing some of the build-out and automation for our purposes.

Automating identification and quantification of mouse scratch behavior in video recordings

Itch is a key symptom of many diseases. Drug development for these diseases requires assessing itch to determine if potential drugs work. We developed a workflow to rapidly quantify scratching, a measure of itch, in a pre-clinical animal model to speed drug discovery.

After putting in a lot of effort — both computationally and experimentally — to figure out what was possible for bioprospecting anti-itch molecules in ticks, we have made the hard call to ice this project. We made a lot of progress in terms of tooling and candidate identification, but ultimately there still remained too many technical and biological unknowns. We needed to define a clearer roadmap for engineering and potentially commercializing therapeutic activity, which wasn’t possible in light of the unknowns.

Trove was our first and longest-running startup incubation project, and we take pride in not only what we’ve learned but in our decision to end the effort. We hope our resources and lessons can be helpful to others. We still believe that this project has potential, and we’ve written up a perspective piece that summarizes our contributions and what additional unknowns need to be solved. Please do not hesitate to leave a comment if you have any questions or are interested in picking up where we left off. Ticks are truly a treasure trove for innovation, and we hope someone can succeed in fully unlocking that potential one day!

Lessons from our approach to bioprospecting in ticks

Ticks produce a trove of bioactive molecules. We built a discovery pipeline to find new therapeutics in ticks, but were stymied by compounding challenges in our approach and decided to ice the project.